Rosy-faced Lovebird / Peach-faced Lovebird (and other Lovebirds) Nest and Roost Site Information Provided by Citizen Scientists.

The photographs and site information in this section are primarily provided by lovebird location reporters. Along with the location report, many users also provide details about where the lovebirds are living nearby and some photographs. This type of infomation gathering is called citizen science. This is very important for a species that lives near people in the middle of urban areas. The most likely source of new information about lovebirds is going to come from people who see them every day in their yard, where they work, or where they like to exercise. You may have important information about lovebirds and not realize it. The majority of lovebirds in Phoenix are Rosy-faced Lovebirds, previously commonly called Peach-faced Lovebird in North America. This name is still recognized, but over time the "world" common name, Rosy-faced Lovebird, will eventually predominate. Many other species of lovebirds are also in the Phoenix area, including hybrids and mutants that have different colors than the original species, but are still lovebirds. However, many of these birds cannot reproduce, although they can often be seen hanging out in flocks with Rosy-faced Lovebirds. Keep in mind that lovebirds are an invasive species of parrot that happens to be well suited to the climate, food, and plants in Phoenix. There are only two major population centers for Rosy-faced Lovebirds in the World, the Southwest part of Africa (Namibia and part of South Africa) and metro Phoenix. Other species of lovebirds come from other parts of Africa and Madagascar. Lovebirds are in Phoenix because people released them in Phoenix and in nearby areas. Why are lovebirds successful in Phoenix? How fast will the population grow? Are there limits to where the lovebirds can live in the Phoenix metro area? If people didn't provide feeders for birds, how would that affect lovebirds? How are native birds affected by lovebirds?

There are currently no native species of parrots remaining in the United States. One species is extinct (Carolina Parakeet), and one species still lives in Mexico, but is no longer found in Arizona (Thick-billed Parrot). The list of invasive species of parrots found in the United States is long and growing. Perversely, some species of parrots may be extirpated in their native lands but still thriving in a North American city or some other city in another part of the world.

|

In the Phoenix area, more reports of lovebirds associated with palm trees are received, compared to any other type of nest or roost location. Lovebirds may use the same location for a nest site (laying eggs and raising young) as well as a roost site (shelter). In this photo, supplied by Brian Sandwich, is an untrimmed Mexican fan palm tree 30 feet in height. Brian reports that this tree, and others nearby, ranging from 30 feet to 50 feet, are homes for lovebirds. The untrimmed palm tree is probably the "classic" model for what lovebirds are looking for when compared to the African acacia tree used by the Sociable Weaver bird. The weaver builds huge grass structures in the acacia tree, and the lovebirds use this for their homes in Africa where the Rosy-faced Lovebird comes from. Parrots are called cavity nesters because they all live in some form of structure, typically a hole in a tree carved out by the parrot or another bird, such as a woodpecker. Only two types of parrots will create their own cavities from grass-like materials, the Monk Parakeet and the lovebirds (there is more than one species of lovebird). An untrimmed palm tree provides these materials. Brian reports the lovebirds in his area frequent untrimmed trees. If a tree is trimmed, they will abandon the tree until the dead branches accumulate. Palm trees should be trimmed outside of the spring and early summer, if possible, to avoid disturbing the nests of the many types of birds that use palm trees to raise their young.

|

|

This Rosy-faced Lovebird was photographed by Brian Sandwich with nesting material tucked into its rump feathers and under the primary wing feathers. This is typically how Rosy-faced Lovebirds carry nesting material back to the nest location. Not all lovebirds carry the material this way; at least one carries the material in the beak. |

|

This is another example provided by Brian Sandwich showing how the nest material is carried by the lovebird.

|

|

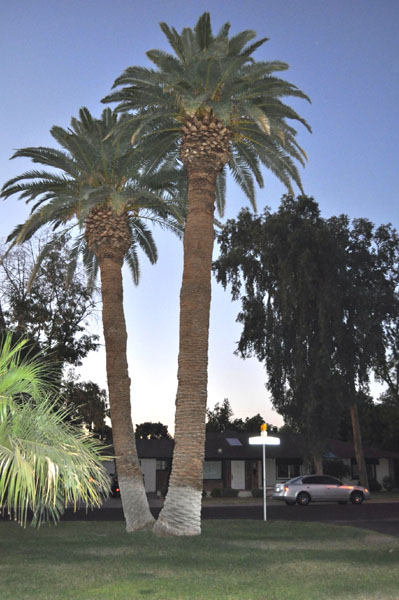

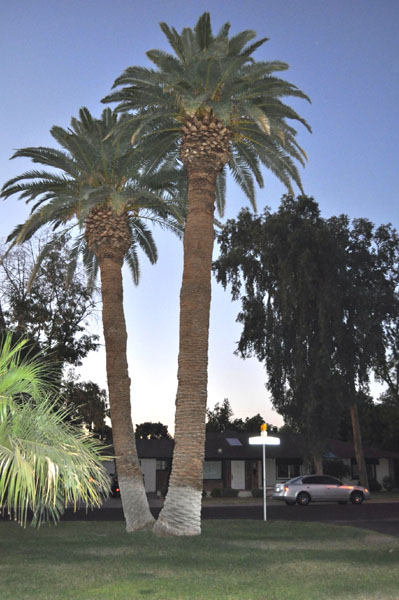

Although untrimmed palm trees would seem to be ideal, and are favored by some lovebirds over trimmed trees, the lovebirds will also use trimmed palm trees. This photo shows a pair of trees that are both utilized by lovebirds. There are several factors that may contribute to whether a tree is used. So far, reports of palm tree size from 25 feet to 50 feet have been reported. Since palm trees can reach much taller than 50 feet, is there an upper limit? Does the preferred height of a tree also depend on whether it is trimmed? Does the density of untrimmed branches matter? The author has seen lovebirds using a single hole in the trunk of a palm tree about 20 feet above the ground. Presumably, this was a Gila Woodpecker-constructed cavity. Is this also a common nest location? In trimmed palm trees, does the nature of the trimming itself provide better access to natural cavities at the base of where the palm frond originates? |

| This photo shows lovebirds using one of the trimmed palm trees shown above. Note that there are cavities in the ends of cut fronds, and these may be used by the lovebirds. There may be other cavities at the bases of the fronds. |

|

|

This trimmed tree shows lovebirds on the trunk and, at the lowest cut fronds, there is green grass, presumably brought by the lovebirds to enhance the nest site. |

|

This photo shows a cavity with one lovebird at the entrance. Other photos at the same location show lovebirds farther in the rear of the cavity, as well as juvenile lovebirds presumably born at the site.

Photo by Najork |

|

Saguaro cactus is also a preferred source of cavities for nest and roost sites. In this photo the cactus on the left, and the left-most cactus arm, is the site used by the lovebirds. Questions remain about the height of the cavity that is preferred. The cavity itself is typically made by a Gila Woodpecker or Gilded Flicker. The cactus forms a scar inside the cactus that resembles a boot; the cactus generally tolerates the cavities that result. These cavities are used by many species of native birds besides the woodpecker that made the hole. Some examples of these other birds are Western Screech-owl, Elf Owl, Ash-throated Flycatcher, Purple Martin, Cactus Wren, and American Kestrel. There is usually some competition for a cavity resource. Because European Starlings, an abundant invasive species, use the cactus cavities, they have a bigger impact on competition for cavities than lovebirds. In a particular location where there are more than 100 lovebirds using cactus, the lovebirds may be using all the cavities in the area. Whether native species can share a saguaro with lovebirds is best determined by people who live near cactus with a lot of lovebirds in residence. It is not unusual for several native species of birds to share the same saguaro. Is this also true for lovebirds?

Photo by Stephanie Beatty

|

|

Adult Rosy-faced Lovebirds at cavities in adjacent arms in a saguaro cactus.

Photo by Sylvia Brongo |

|

This photo represents one of the "other" categories where lovebirds are known to roost and nest. Besides palm trees and saguaro, roof tiles have been reported numerous times (no photo of one of these yet). What is not reported is a possible site in a big tree. This happened in 2014, and the photo shown here is probably that of a Shamel Ash. The location reporter has observed the lovebirds coming and going at the very top of the tree. No structure has been observed so whether the nest location is in a cavity in the trunk, or is in a woven material nest built by the lovebirds, is not known. It is reported that there is a continuous lovebird presence in the tree, and the lovebirds are very vocal. A second location has also been identified for this same type of tree in a different location in Phoenix. Apparently at this second location, although there is a large number of lovebirds present at all times, it is known that there is no nest of any kind present. |